Robotics Replaces Some Workers, But Hand Work Remains Necessary

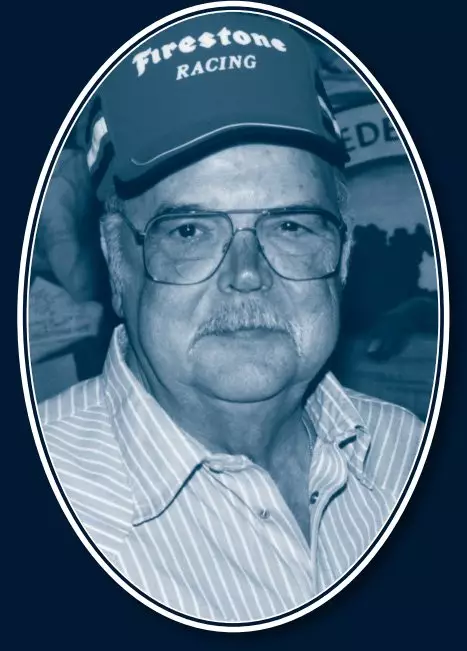

When Diamond Star Motors began production in 1988, the assembly line included state-of-the-art robotic arms that did 90 percent of the welding. Fortunately there were still many jobs for workers.Featuring:Dan Nelson, (1949 – 2004), assembly line at MitsubishiCharlie E. Gordon (1933-2014) and Ralph Walden (1933-2008), Firestone tire manufacturersDan Nelson (1949-2004) earned a teaching degree from ISU and taught grade school for 11 years. But at that point he was ready for something else. Dan worked as a woodworker for Prairie Woodworks for seven years, but in 1998 decided he could make more money as a metal finisher at Bloomington’s new automobile factory — Diamond Star Motors (DSM).

Using a grinder, referred to by workers as a “chainsaw,” Dan ground down and smoothed welds on cars as they came down the assembly line from the body shop. In 1992 union workers at Diamond Star Motors, like Dan, earned $17 hourly ($20 if they were skilled) plus benefits. In 1995 Diamond Star Motors reorganized to become Mitsubishi Motors North America. That same year Dan was among the employees who celebrated the millionth car to come off the line.

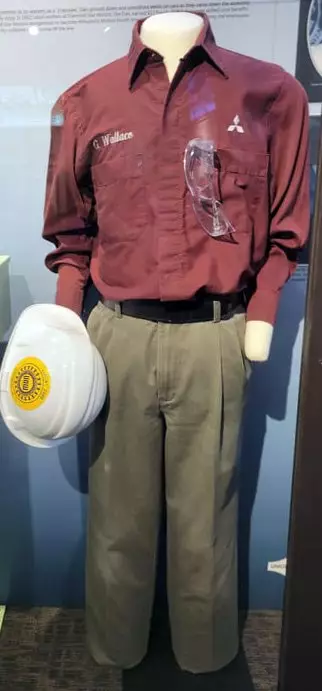

Mitsubishi uniform shirt, hard hat, goggles, circa 1998

View this object in Matterport

Mitsubishi workers were required to wear a uniform like this one worn by Glen Wallace, one of the original employees hired by DSM. When the plant closed in November 2015, Glen was one of approximately 1,200 workers, producing about 70,000 cars annually.

Donated by: Glen Wallace

2017.19.02, 2016.20.01, 3

Mitsubishi / DSM pneumatic grinder, circa 2000

View this object in Matterport

Donated by: Mitsubishi Motors

2016.20.06

Palm button assembly line controller, circa 2000

Palm button controllers were located at every station for starting and stopping the assembly line. Because safety was important, workers needed both hands on two separate buttons in order to restart movement of the line. This one was used on the line when the Outlander Sport was manufactured.

Donated by: Mitsubishi Motors

2016.20.12

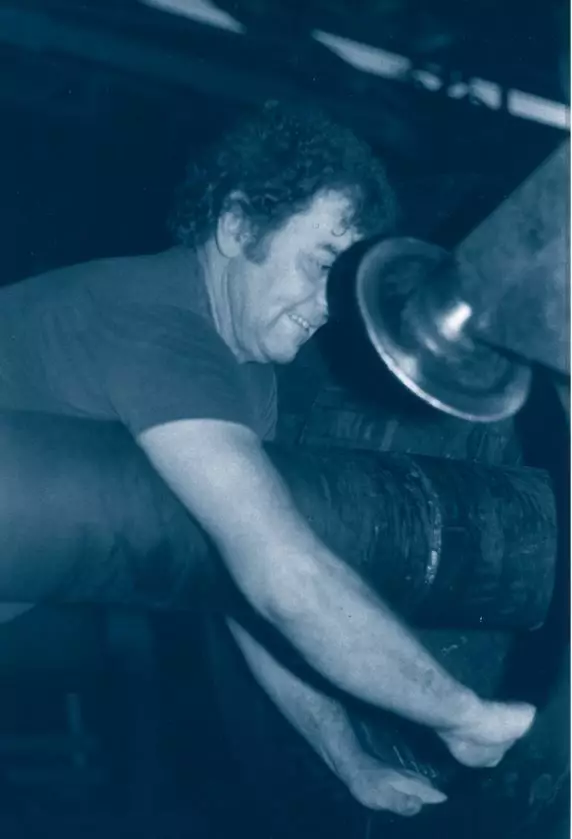

When workers at Bridgestone-Firestone’s Normal plant began building large tires, hand work ensured a quality product.

Charlie E. Gordon (1933-2014) and Ralph Walden (1933-2008) became lifelong friends after they began making off-road tires together at Bloomington’s Firestone factory.

They both built tires by first layering strips of thick rubber on a rotating metal drum. The barrel-shaped layers were then heated in a mold to give the tire its shape and to cure the rubber.

Working at Firestone had its downsides. The smell of hot rubber and chemicals was one that permeated Charlie and Ralph’s clothes and skin. Ralph noted that anyone who had ever been inside the factory knew that smell.

“I went in the store one time . . . A woman asked me, ‘Do you work for Firestone?’ I smelled horrible.”

— Ralph Walden

Ralph, Charlie, and their coworkers built some of the largest tires in the world — used on off-road mining and construction equipment.

Charlie layered plies of nylon cording embedded in thick rubber onto a tire mold, creating a barrel-shaped structure.

The tire was then pressed into a huge mold with a large domed lid called a pot heater. Inside the mold the tire was compressed and heated with steam. Called vulcanization, the heat created a chemical link between the layers of rubber, a process that took up to 22 hours depending upon the size of the tire. The tire above and to the left are Firestone’s 70/70-57. In 2017 this tire was the largest tire made in the world and took 40 workers 88 hours to complete.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County