Building for a Growing Population

A growing community in need of housing meant a greater need for workers in the construction trades.Featuring:Kirkpatrick “Kirk” Buffham, (1844 – 1895), painterAlfred Carlsson Lundeen, (1862 – 1927), furniture makerCharles Mott, (1847 – 1923), Brick & Tile Company laborerPeter C. Duff, (1856 – 1919), African American carpenterKirk’s skills were in demand. The faux graining of inexpensive woods, like pine and ash, to look like higher quality woods, such as oak, was very popular at the time.

Kirk knew how to effectively apply layers of paint and then comb them with this special tool to get the desired effect. He also knew how to mix and apply calcimine, a calcium-based paint that when applied to a plastered wall gave it a bright white color that lasted. He could also add pleasing decorative elements or stenciled designs to interior walls. These skills he also used to create signs.

Around 1868 Kirk partnered with Bailey Plumb. They expanded their business by opening a paint supply store.

They ended their partnership in 1873, when Kirk’s brother, George, joined him in the business. They had a successful partnership until Kirk died in 1896. George continued to run the business until 1905.

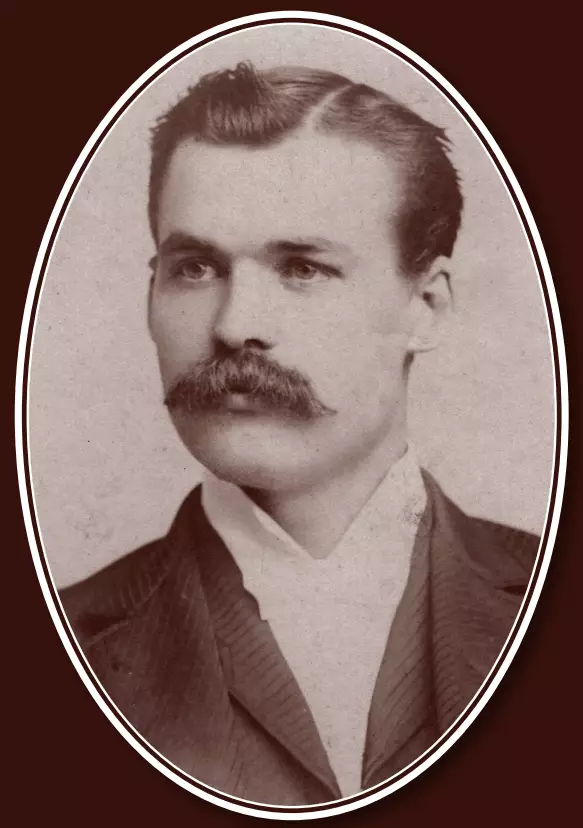

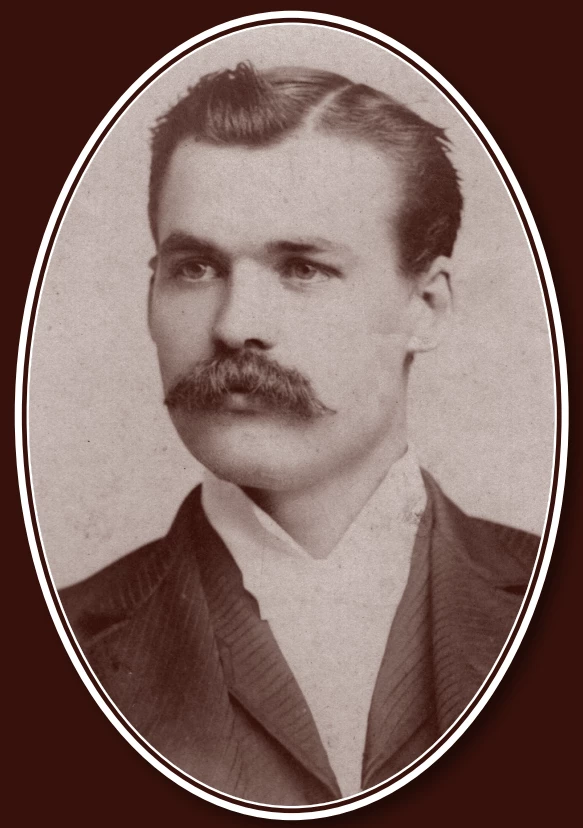

Alfred Carlsson Lundeen

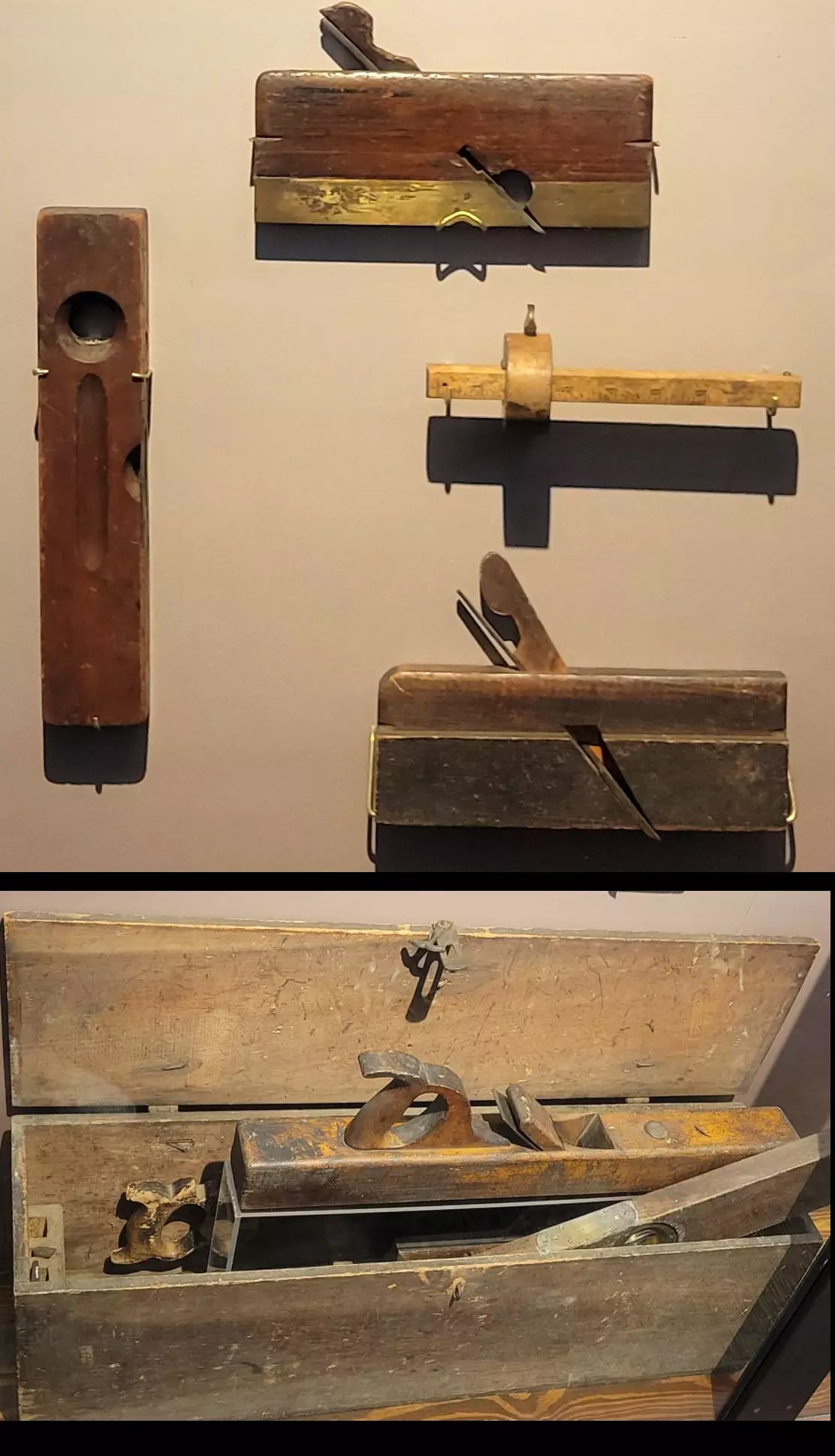

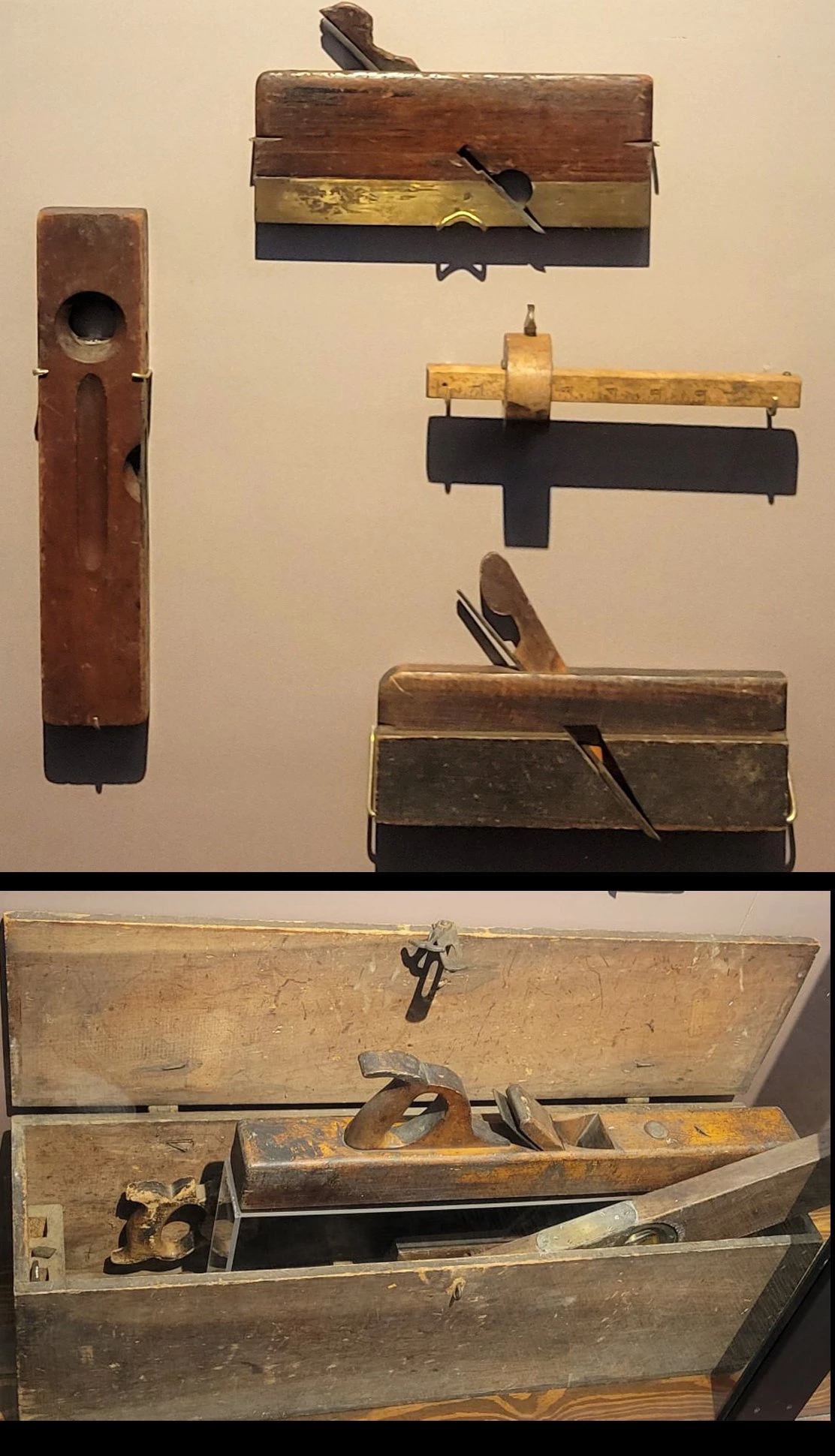

Alfred Carlsson Lundeen (1862-1927), a Swedish immigrant woodworker and furniture maker, settled in Bloomington in 1888.

Alfred hoped to make it as an independent furniture maker. But with the railroad bringing in ready-made furniture, he knew it would be a challenge.

Do you think Alfred was successful?

Alfred and his coworkers ran the saws, planers, and lathes used to cut and shape wood into lumber and trim pieces. These products were sold to carpenters and builders to be used for constructing new homes.

Moratz's mill became the Acme Planing Mill in 1911. Alfred retired from Acme around 1924.

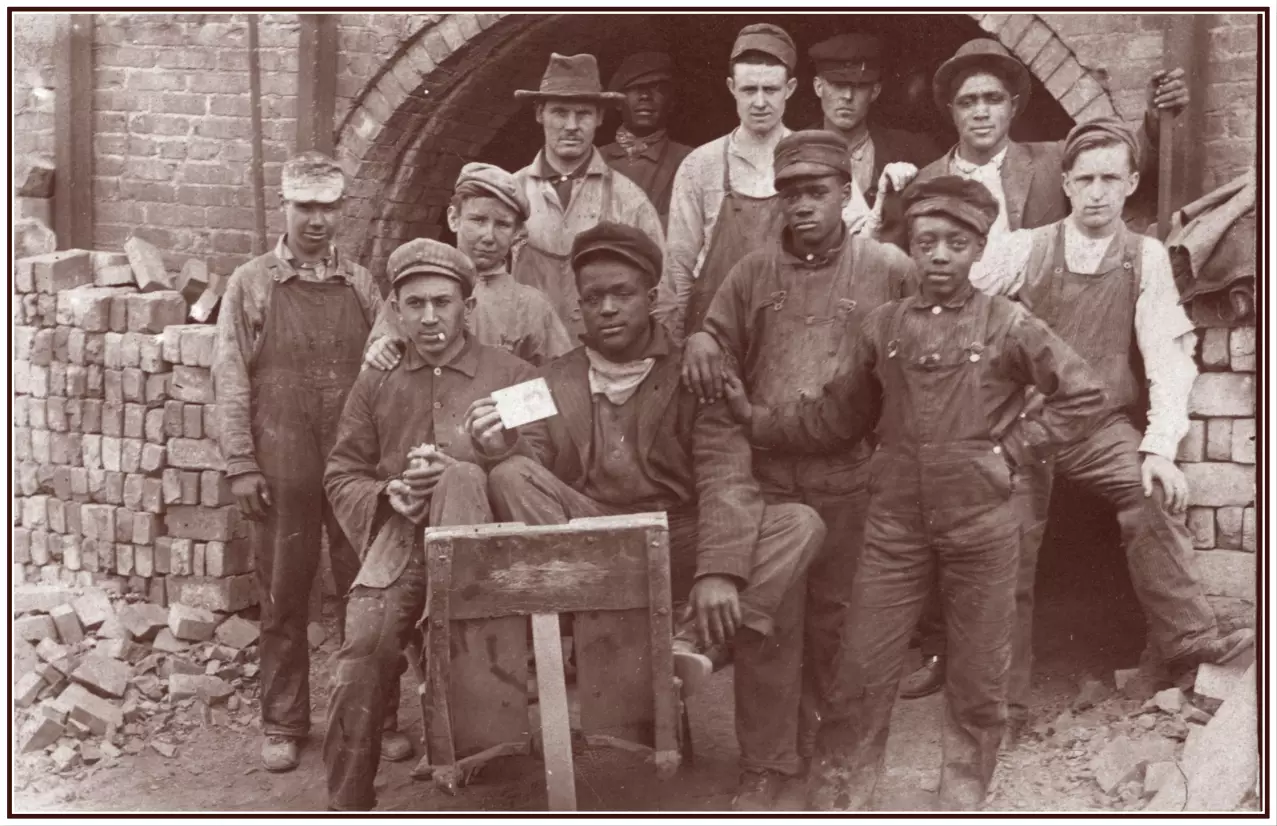

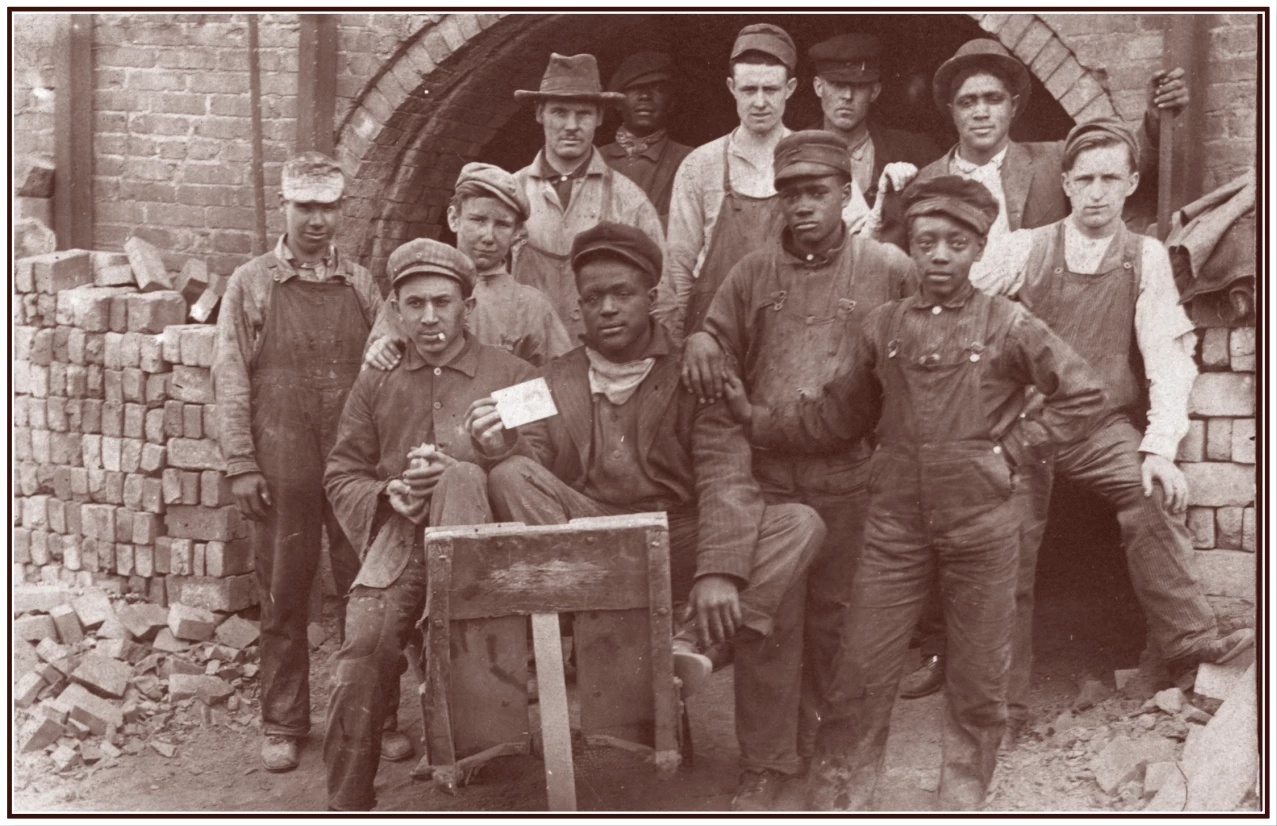

Charles Mott

Charles Mott (1847-1923) came to McLean County from New York with little education and few skills.

He found work as a laborer at the Bloomington Brick & Tile Company around 1870.

Charles’ work was seasonal as winter was not the optimal time to dig clay from the ground — the first step for making bricks.

Charles and the brickyard’s other laborers worked the clay by hand (much like kneading dough) to remove air bubbles, then pressed the worked clay into molds. As the clay dried, the bricks shrank and the molds were removed so the bricks could dry completely.

Next Charles carried the bricks to the kiln to be baked. After they cooled, the fired bricks were removed from the kiln and stacked. Keeping the kilns burning during summer months was challenging work. With the interior temperature of the kilns reaching 1,800 degrees, the area surrounding them was extremely hot.

The Bloomington Brick and Tile Company was one of three area brickyards started by Thomas William Van Schoick, who came to Bloomington in 1858 to increase his fortune. He knew the area was growing rapidly and that money could be made manufacturing bricks to meet business and home construction needs. He employed 300 to 400 seasonal laborers at his factory.

Because brickmaking was seasonal, Charles had to find other work during the offseason.

What kind of work do you think Charles did when the brick factory was not making bricks?

With the community growing, hard labor jobs were always available for those with little education or training, including construction, railroad yards, or seasonal farm work. We don’t know what Charles did. But we do know that he did not stay in Bloomington.

Peter C. Duff

Enslaved until emancipated, Peter C. Duff (1856-1919) came north from Kentucky in 1870.

It was always difficult for African Americans, like Peter, to find work that was not labor. It was even more challenging to get an education.

Could where he decided to settle have made a difference?

Peter settled in Normal where African Americans were welcomed. He found work with the Jesse Fell family — an extremely fortunate circumstance for a 14-year old, as Fell required all those who worked for him to get an education. Peter also learned and became proficient at the carpentry trade while working for Cunningham & Kofoid, prominent Normal contractors who built homes.

When the City of Bloomington decided to build a concrete reservoir on the northwest side of town, Peter’s carpentry skills proved a valuable asset.

Peter’s work on the reservoir project led to work with the Chicago & Alton Railroad.

Brick railroad bridges built in the mid-1800s needed to be replaced. Peter constructed the forms needed for new concrete supports.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County