Producing for an International Market

Featuring:George Hoagland, African American inventor and factory ownerHenry Conrad, cobblerFrank C. Abbott, (1859 – 1926), soda entrepreneurThe orphaned son of a Kentucky slave, George Hoagland (dates unknown) worked hard all his life. In 1889 he made his way to Normal, where Black people were welcomed and he could get an education.

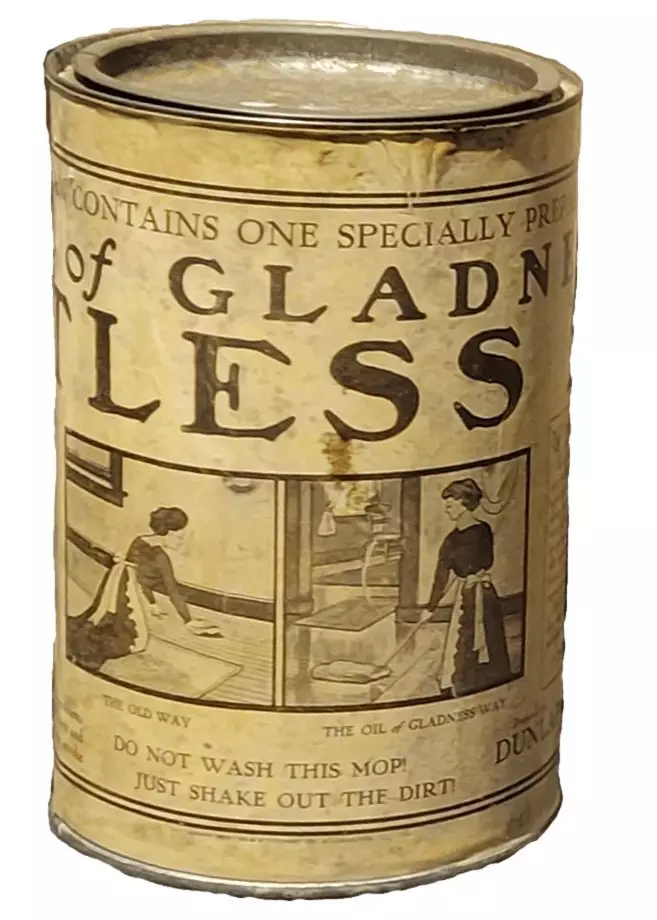

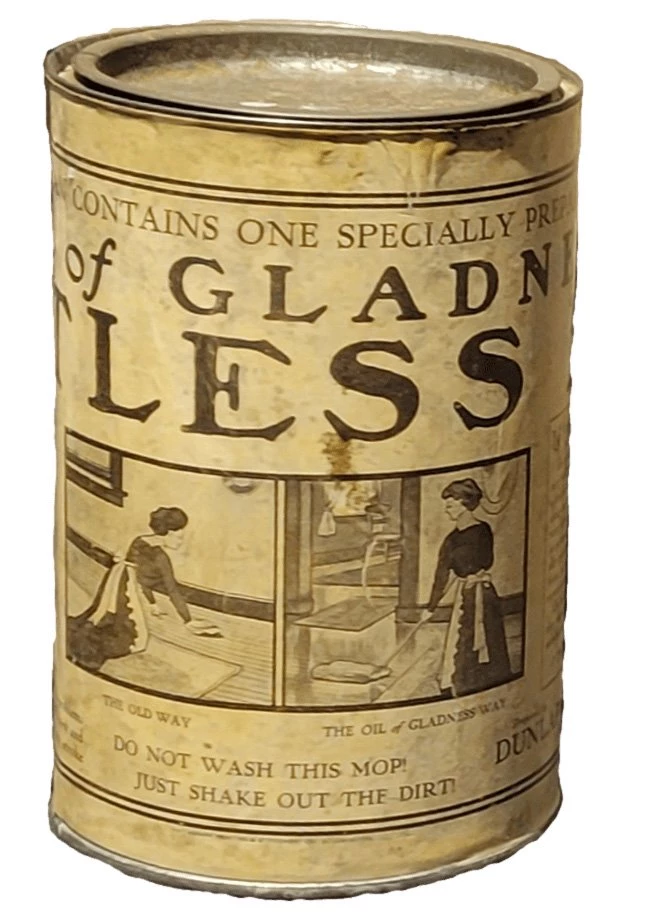

George found limited work as a laborer. But while working as a janitor, he began to experiment with different oils in order to make cleaning linoleum floors easier. The result was “Hoagland’s Oil of Gladness.” In 1907 George began production. He hired African American workers at his factory on West Washington Street.

Owning a business was not easy for an African American. Predjudices made it difficult for George to sell his product.

Was there a way that he could have eased this challenge?

In 1909 George contracted with a white-owned business, the Dunlap Manufacturing Company, to produce, market, and sell his products.

George left Bloomington in 1915 to pursue his work as a minister, having sold his business to Oliver and Dunlap. They sold to a Sheboygan, Wisconsin company in 1920. The Bloomington plant closed in 1922.

A Christian minister, George referenced his religious beliefs by using a line from Psalm 45 of the Bible, “Thou lovest righteousness, and hatest wickedness: therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee with the oil of gladness above thy fellows,” in naming his products.

Some manufacturers made their living crafting one-of-a-kind items and products to be sold locally.

Henry Conrad (dates unknown) arrived in McLean County by 1853 and established a shoe shop in a Bloomington location recently closed by another cobbler. He was one of 10 shoemakers in town who cut and sewed ready-made shoes and custom-made shoes.

Competition between these craftsmen tended to reduce profits, as the best way to attract customers was to offer lower prices.

Can you think of a way Henry and the other shoemakers might have tried to change this?

In November of 1853 the city’s shoemakers met and organized the Boss Boot & Shoe Manufacturers of Bloomington.

The organization’s goal was to ensure they could all make a living. They did this by agreeing on specific prices for their products, which they published in the Pantagraph. With fixed prices in place, competition depended upon the quality of the materials used and the skill of the shoemaker.

Henry continued to run a shoe shop until 1869 when, like the previous shop owner, he left town.

“The undersigned have agreed not to sell or cause to be sold, barter, or exchange, at retail, work of their own manufacture, for less than the prices herein agreed upon.”

— Bloomington Weekly Pantagraph, November 16, 1853

Henry would have used tools like these to craft the shoes he sold in his shop.

Frank C. Abbott (1859-1926) did not like his first jobs as a miner and timekeeper for the Bloomington Cooperative Coal Company. So in 1887, at the age of 28, he partnered with S.B. Cooper to start the Excelsior Bottle Works.

Frank combined and bottled carbonated water mixed with flavored syrups, offering a variety of flavors, including: lemon, cream, strawberry, sarsaparilla, ginger ale, and pear cider.

Excelsior soda bottles with patented Hutchison stoppers, circa 1895

Frank’s challenge was to keep the soda carbonated. Excelsior bottles used a patented Hutchison stopper that fit inside the bottle beneath an interior lip. Carbonation pressure kept the bottle sealed, while the curved spring that stuck out of the bottle could be pushed down to open it. Both the bottle and stopper could be reused, if properly cleaned.

Donated by: John Colteaux

818.201, 728.5

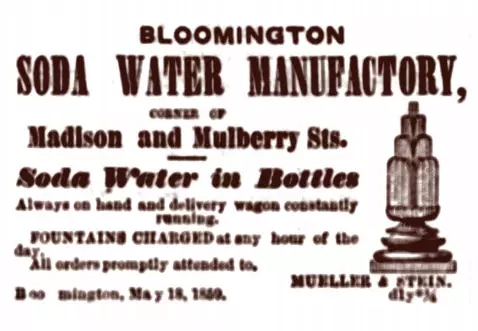

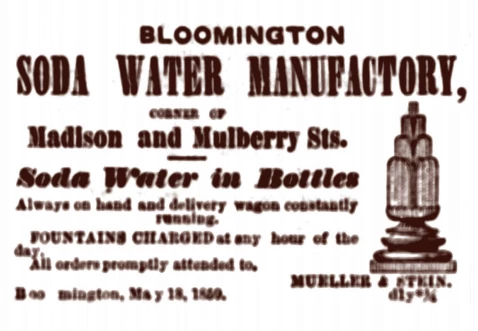

Frank was not the first person to offer bottled soda to Bloomington residents.

What year do you think soda first became available?

Was it 1838, 1848, 1855, or 1868?

Bottled soda was available as early as 1855, but cork stoppers (if they stayed on) did not hold in the carbonation. R. Thompson & Company installed Bloomington’s first soda fountain in its drug store in May 1858.

In 1891 Frank hired William F. Schuck, who had worked for the competition, to help with bottling. Eight years later, when Frank decided to move to Minnesota, he sold the Excelsior Bottle Works to Schuck, who carried on the business until 1916. At that time he sold it to the Peoria Coca-Cola distributor.

Making a Home

Making a Home

A Community in Conflict

A Community in Conflict

Working for a Living

Working for a Living

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Farming in the Great Corn Belt

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County

Abraham Lincoln in McLean County