Although nearly forgotten today, Bloomington-born artist Sid Smith was a towering figure in American popular culture. From 1917 until his untimely death in 1935, Smith’s newspaper comic strip “The Gumps” was a cultural touchstone, read by millions each day from coast to coast.

Robert Sidney “Sid” Smith was born February 13, 1877, in Bloomington. His father, Thomas H. Smith, was one of the city’s earliest and most successful dentists. He was also a lumberman, operating a sawmill outside the city limits.

Smith lacked his father’s academic and entrepreneurial drive, and when he was around 12 years old (or so the story goes) his teacher gave him the following advice: “You go home young man. You’re not fit for anything but a cartoonist.” Smith, as he recounted years later, felt “morally insulted” because he had no idea what a cartoonist was.

Apparently, Sid Smith attended but never graduated from Bloomington High School “My father wanted me to be a dentist,” he recalled. “But to be a dentist I had to study, and school and I never agreed: they didn’t teach drawing where I went. I was about 17, I think, when I saw a schoolroom for the last time.”

Smith’s artistic talent, though, was never in question, and soon he found a local audience for his drawings. When he was 18 or so he began contributing sketches and cartoons to The Sunday Eye, an illustrated weekly newspaper published in Bloomington.

“From the start I was crazy to draw pictures and see how they would look reproduced in the newspapers,” he remembered. Failing to land a full-time position he became an itinerant “chalk talker.” He would travel from town to town, entertaining audiences with light chat and whimsical sketches. When money was short, he would hop a freight train to the next town. “My only equipment was chalk, a blackboard, and nerve—chiefly nerve, no money,” he said of his year-long, cross-country tour. “I saw life in a thousand aspects that have been of help to me since.”

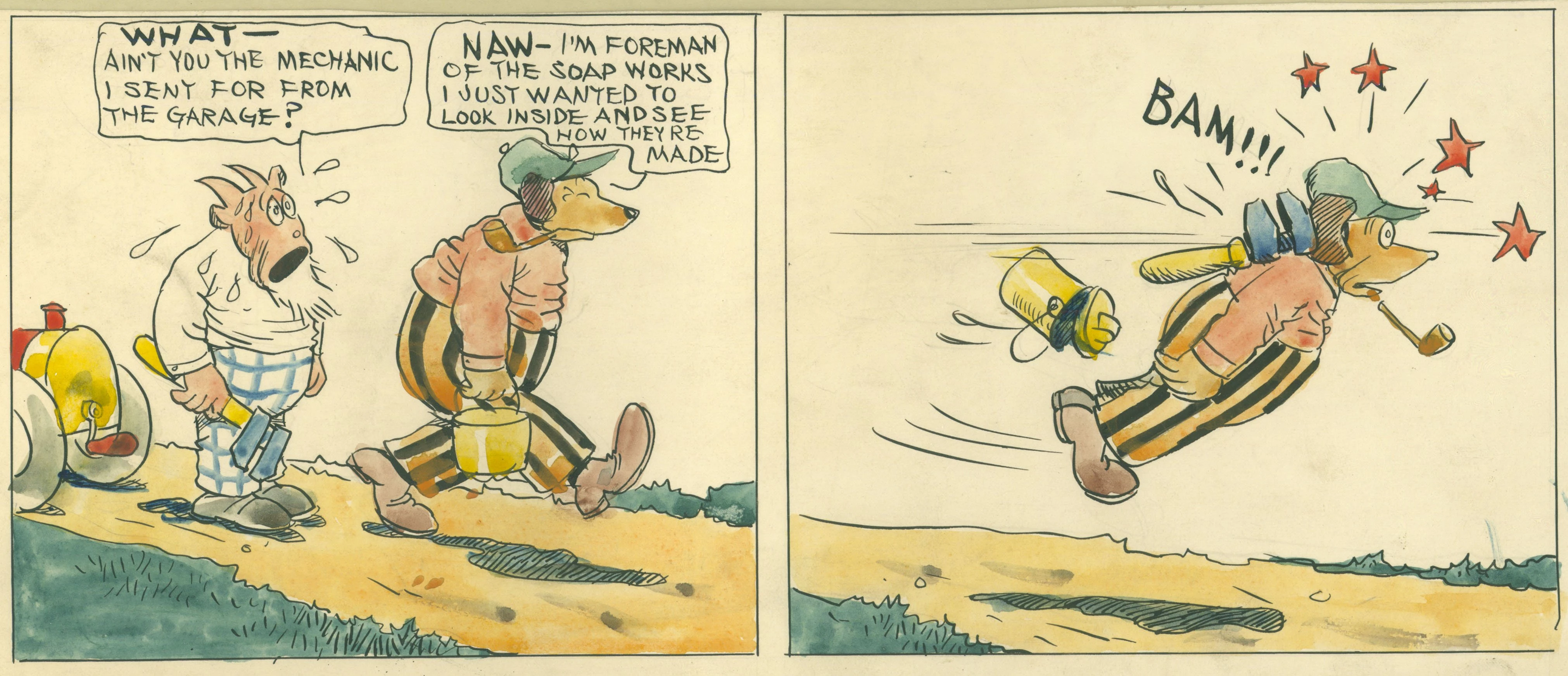

Smith then bounced from one newspaper to another in places like Indianapolis and Pittsburgh before settling down in Chicago, first with the Examiner and then, in 1911, the Tribune. Smith enjoyed success with “Old Doc Yak,” a Sunday-only strip that celebrated the gentle misadventures of the goat-headed “Doc Yak” (see accompanying two panels).

In 1917, Smith unveiled “The Gumps,” a strip featuring the chinless patriarch Andy, his wife Minerva (or “Min”), their son Chester, and a cast of lovingly rendered supporting characters, ranging from Tilda the maid to wealthy Uncle Bim.

“The Gumps” was said to be the first major strip to move away from the “joke-a-day” format toward one with a narrative flow. “You don’t draw cartoons, you write ’em,” Smith would say. Guided by Tribune publisher and coeditor Joseph Medill Patterson, Smith fashioned a comedic soap opera of domestic life carried by storylines that stretched for weeks. It was a revolutionary advance in the comic strip medium that would prove wildly popular with the reading public.

Andy Gump represented “a kind of everyday philosopher,” Smith once said. “He tries to voice the sentiments of everyday people. My idea is to make him the sort of chap so that people can hold a mirror in front of themselves and say truthfully: ‘There’s Andy Gump.’”

In the spring of 1922, Smith signed a $1 million contract—$100,000 for 10 years guaranteed—with the Tribune. As a bonus he received a Rolls-Royce (he also lobbied for, and eventually received, an oriental rug for his office). At the time, the highest paid comic strip artist was Bud Fisher of “Mutt and Jeff” fame, who was paid $50,000 a year.

Two months after signing the record contract Smith motored through Bloomington in his Rolls, with The Pantagraph reporting that “the new machine attracted much admiring attention on the streets.” His Smith’s license plate number was “348,” the same as Doc Yak’s and Andy Gump’s.

Smith liked to live the high life, and he divided his time between a Gold Coast residence; an estate on the south shore of Lake Geneva, WI; a smaller place he called “Forty Acres” near Genoa City, WI; and a 2,200-acre farm in the northern Illinois community of Shirland.

In 1929, Smith killed off supporting character Mary Gold, and this act of artistic fratricide caused such an uproar that the Tribune hired additional help to handle the deluge of mail and phone calls. Eighty years later, this death is regarded as a seminal event in the maturation of the comic strip as a popular art form.

Sadly, R. Sidney Smith’s life was cut short when, in the early morning of October 20, 1935, he died in a head-on automobile accident not far from his farm in Shirland.

After Smith’s death, Tribune sports cartoonist Gus Edson continued “The Gumps,” and although the strip lasted until 1959, its popularity never reached its earlier heights.