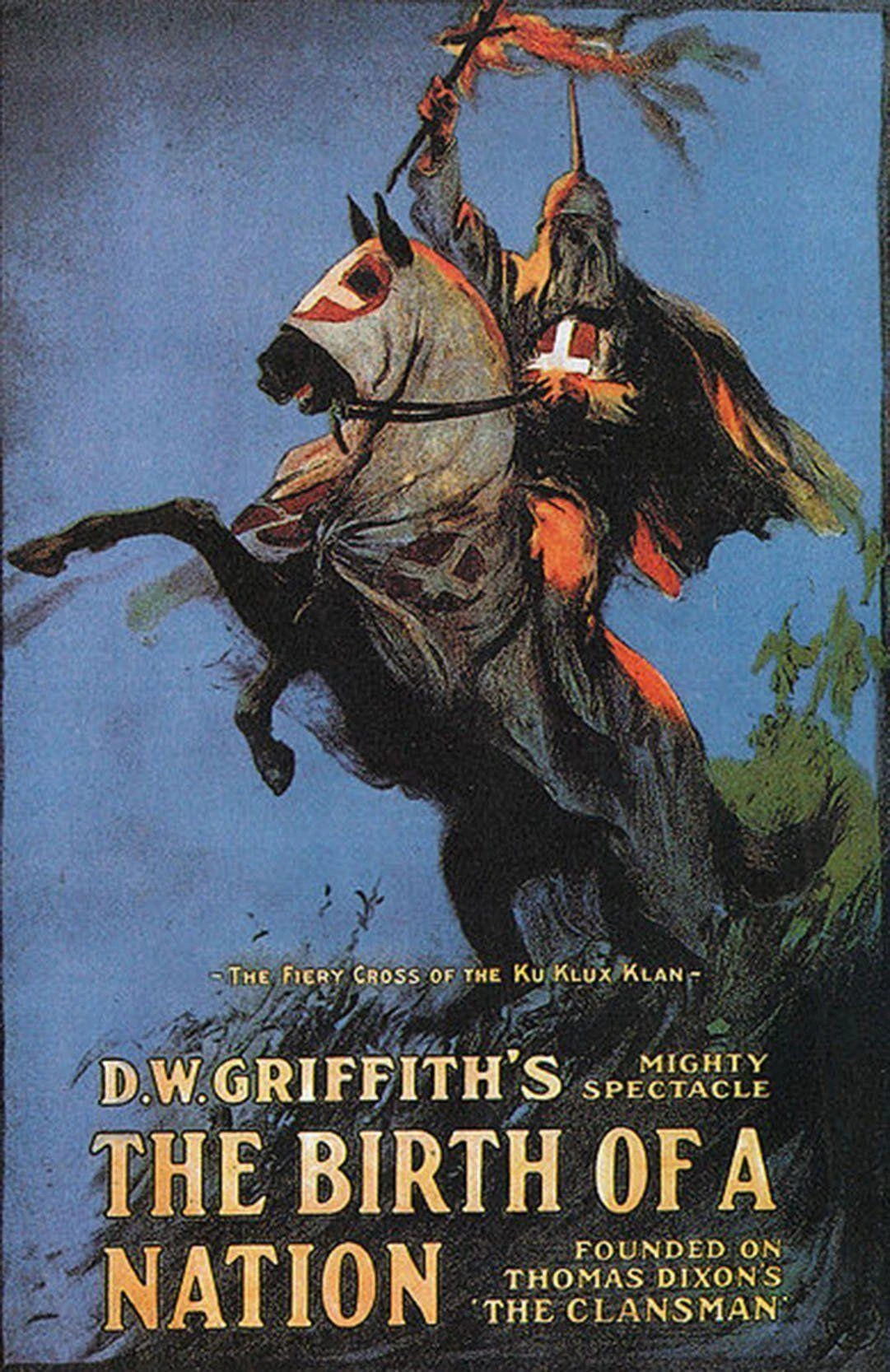

The 1915 silent film “The Birth of a Nation” is acclaimed today as one of the greatest achievements in motion picture history. At the same time, and by many of the same critics and film historians, it’s also reviled for its sickening racism.

A paean to the Ku Klux Klan and an unrepentant South after the Civil War, filmmaker D.W. Griffith’s 133-minute epic offered spectacle on a scale never before seen on the silver screen. He employed a cast of thousands for sweeping battlefield set pieces that remain a technical and artistic marvel today. He also pioneered many camera techniques, including the panning shot, close-up and panoramic long take.

Then again, this technical artistry served a profoundly racist interpretation of the era after the Civil War known as Reconstruction. In this retelling, the Ku Klux Klan was not a terrorist organization murdering and maiming thousands of African Americans guilty of nothing more than seeking their constitutionally guaranteed rights and a measure of human dignity.

Instead, the hooded Klansmen were depicted as heroes who restored white rule, putting an end to a brief period when African Americans were able to vote and hold elected office in the Deep South. African Americans or white actors in blackface were portrayed in grotesque fashion involving all the ugliest racist tropes, especially black males as sexual predators.

Released in early 1915, “The Birth of a Nation” arrived in Bloomington on Thursday, Jan. 27, 1916, for a three-night run. It played at the Chatterton Opera House, a theater originally built in 1910 for live entertainment. The old building still stands today on East Market Street immediately west of Lucca Grill.

“Nothing like it since the dawn of civilization,” screamed an advertisement for “The Birth of a Nation” in The Pantagraph. “Most stupendous, most realistic, most convincing, most exciting, most absorbing, most dramatic narrative ever created for the edification of the American people.”

“Edification” of the wrong kind is what worried African-American leaders and those interested in racial equality. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), for instance, organized protests in New York and elsewhere.

Despite its unabashed racism (or perhaps because of it) the film triumphed at the box office. There was even a screening for President Woodrow Wilson at the White House.

In certain instances, the depiction of black depravity whipped thuggish whites into a fervor who would then seek out unsuspecting blacks for harassment or beatings. There were also riots in Boston and Philadelphia, among other cities.

On the eve of the Jan. 21 Bloomington City Council meeting, The Pantagraph reported that the local African-American community planned to voice its opposition to the film with a petition. “It is claimed by the circulators of the petition,” noted this newspaper, “that the film has caused race prejudice and hatred in many places, and created prejudices against the Negroes wherever shown, and on this account they want it prohibited here.”

There was even talk of council members traveling to a nearby city where the film was already playing so they could better judge its alleged inflammatory content.

Yet there would be no mention of the petition in news coverage or published council proceedings, not for the Jan. 21 meeting or any of those following. Why the petition was apparently never presented is not known. Perhaps pressure was placed on African-American leaders to withdraw the protest, or perhaps they decided that such a protest was little more than tilting at windmills.

Locally, African-Americans weren’t the only ones to protest “The Birth of a Nation.” On Jan. 24, the William T. Sherman post of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a national organization of Union Army veterans, adopted resolutions calling for the city to prohibit its showing. At issue for the Bloomington GAR post was not the portrayal of African Americans, but rather its portrayal of Union Army enlisted men and officers.

At a time when local movie prices typically ranged from 5 to 25 cents, tickets for “The Birth of a Nation” at the Chatterton ran as high as $2 (or the equivalent of $43.50 today, adjusted for inflation). Even so, most of the Bloomington shows were sold out well in advance. “The box office at the Chatterton opened yesterday morning on what is, in all probability, the most remarkable seat sale in the history of local theatricals,” remarked the Jan. 25 Pantagraph.

Rural and small town residents were also swept up in all the excitement. “LeRoy was deserted all day Saturday [Jan. 29] on account of the citizens all going to Bloomington to attend ‘The Birth of a Nation,’” read a typical dispatch.

In response to the disheartening popularity of “The Birth of a Nation,” national African-American leaders talked of supporting a similar big-budget epic. Promoters envisioned “The Birth of a Race,” as the planned film was to be called, as a celebration of the vibrancy and resiliency of the black “race.”

Birth of a Race Photoplay Corp. issued stock to finance the film, with liberal-minded folk, white and black alike, buying shares less as an investment and more as a statement against racial prejudice. One such individual was Bloomington dentist John A. Moore, who purchased 10 shares at $10 each in December 1917 (The collections of the McLean County Museum of History include Moore’s stock certificate.)

“The Birth of a Race” had a troubled production history and by its late 1918 release the message of racial uplift had been discarded for the more traditional, less-threatening story of the American victory over Germany in World War I. All the same, the film was evidence that many Americans did not embrace Griffith’s delusional and dangerous misinterpretation of American history, either as fact or entertainment.

In May 1919, “The Birth of a Race” had a six-day run in Bloomington, though it proved a far weaker box office draw than “The Birth of a Nation.”

Griffith’s 1915 spectacle remains a landmark work in motion picture history. Contemplating its social, political and moral complexities, the late Chicago film critic Roger Ebert said “The Birth of a Nation,” was not a bad film in defense of evil, but rather a great film in defense of evil. “To understand how it does so,” he added, “is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil.”