One hundred and forty years ago this week, on Sept. 18, 1879, the incomparable Sojourner Truth spoke at Second Presbyterian Church in downtown Bloomington.

The elderly but still spry civil rights activist and suffragist—who at the time was in her early 80s—was passing through Central Illinois on her way to Kansas to survey the progress made by African-American “Exodusters” fleeing the violence and repression of an unreconstructed South.

For reasons lost to time, Truth, while in Bloomington, stayed at the East Chestnut Street residence of George S. Smith, who was manager of Durley Hall. Initially, there were no plans for her to lecture in the city, but soon enough a call went out (the 1897 talk is believed to be Truth’s only public appearance in the Twin Cities.)

“Even at her advanced age, she regularly lectures every day, and is strong in her sentiments supporting the ‘old Union,’” noted the Bloomington Daily Leader newspaper. “If a suitable place could be provided for her in the city, she would deliver her lecture on Thursday night [Sept. 18] of this week.”

Second Presbyterian Church proved to be a “suitable place” for Truth to speak, which made sense given the congregation’s anti-slavery history and attachment to progressives causes.

Born enslaved as Isabella Baumfree about the year 1797, in upstate New York, Sojourner Truth spoke only “low-Dutch” until she was nine or so years old (this was at a time when slavery was still practiced in much of the North.) In 1826, she escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, and several years later secured the freedom of a son enslaved in Alabama.

In 1843, Isabella Baumfree took the powerful name Sojourner Truth.

Although she never learned to read or write, Truth became an indispensible moral voice for the abolition of slavery and later African-American civil and political rights in the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction eras. She also advocated for other progressive issues—from prison reform to women’s suffrage.

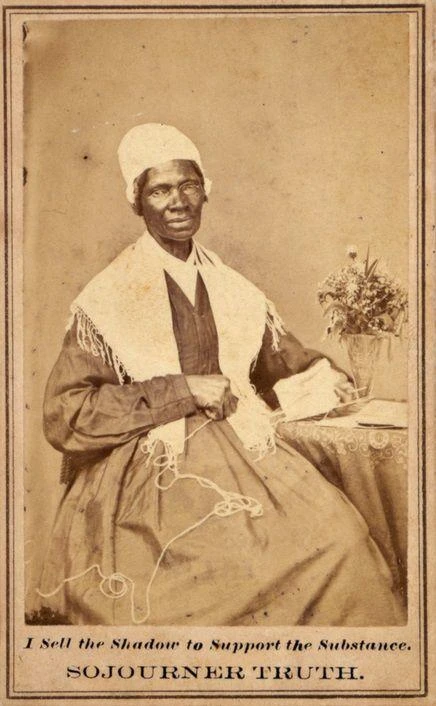

Upon paying Truth a visit before her Bloomington talk, a Pantagraph scribe found the “aged Christian and philanthropist” relaxing in a rocking chair and chatting with friends and admirers. “She was plainly dressed … a white silk handkerchief tied loosely over her shoulders, and a white cap upon her head,” related the reporter. “To her the paths of literature and science were forever closed, but despite the double burdens of poverty and the bane of caste, she has acquired fame and gained friends and admirers among the noblest and best in the land.”

Sojourner Truth was known as the “Libyan Sibyl,” a reference to the prophetic priestess of Classical mythology who foretold the “coming of the day when that which is hidden shall be revealed.”

The deadlocked 1876 presidential election ended with the so-called Compromise of 1877 whereby the Republican Party surrendered federal supervision over the former Confederacy in exchange for four more years in the White House. The withdrawal of U.S. troops and oversight authority accelerated the return of white racist rule, economic subjugation and terror, and the spread of ever-more pernicious Jim Crow laws (that’s why the Compromise of 1877 is also known as the “Great Betrayal.”)

Given such conditions in the Deep South, African Americans looked to migrate to the Great Plains and elsewhere for their rightful piece of the American pie.

“Exoduster” was the term given to southern black refugees, mostly from the states of Mississippi and Louisiana, leaving the Deep South mainly for Kansas, but also for Oklahoma and Colorado (“exodus” refers to the Old Testament flight of the Jews from Egypt.) It’s estimated that some 40,000 Exodusters participated in the “Exodus of 1879” (though the migration lasted more than one year.)

“It is her present purpose to visit Kansas and look over the Exodus Movement, which she has watched with much solicitude, and desires to look into with her own eyes,” stated The Pantagraph. “Her desire to visit the scene of its operations is not only natural but commendable, and her intention to ‘lecture’ her way out there, (she has no other means) will doubtless meet an encouraging response from all philanthropic people.”

At Second Presbyterian Church, Truth lectured for an hour and a half. Her talk, noted The Daily Leader, was “humorous, practical, and full of wisdom.”

The Leader also reprinted a few of her “sayings” from the Bloomington talk. “The beginning was when the first wrong was done, and the end will be when wrong doing is stopped,” she said at one point. “Ministers preach Christ and him crucified; they should rather preach Christ alive and risen in men,” she said later on.

“Sojourner also prides herself on a fairly correct English, which is in all sense a foreign tongue to her, she having spent her early years among people speaking ‘Low Dutch, N.Y.,’” observed The Pantagraph. “People who report [on] her often exaggerate her expressions, putting into her mouth the most marked southern dialect, which Sojourner feels is rather taking an unfair advantage of her.”

Yet the following spring, The Pantagraph did just that in a column of brief news and advertising notices. “Sojourner Truth,” declared this paper, “says she has prayed for years that the colored people would pack up and ‘just leave dat’ar wicked Souf.”

Later this week, on Wed., Sept. 18—exactly 140 years to the day of the Bloomington lecture—Second Presbyterian Church will hold a Sojourner Truth Celebration. The highlights will include historical reenactor Patricia James Davis of Springfield portraying Truth, and gospel music from the combined choirs of Second Presbyterian and Mount Pisgah Baptist churches.

The program—free and open to the public—begins at 7 p.m.

Sojourner Truth is one of five women associated with the American suffrage movement who will begin appearing on the back of the $10 bill by sometime next year.

Or at least that’s the hope, for the current presidential administration recently announced the inexplicable postponement until 2028 of similar plans to replace Andrew Jackson with Harriet Tubman as the face of the $20 bill. Tubman escaped slavery and then helped hundreds of other enslaved individuals make their way to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

“Her memory is still remarkable,” a Pantagraph reporter said of Sojourner Truth back in 1879, “and flashes of wit and wisdom still emanate from her soul like the rays of the natural sun as it bursts forth from a somber cloud, baptizing earth and sky with the radiance of its expiring glory.”